Steam Boilers: Structure, Operating Principles, and Industrial Importance

Steam boilers serve as the beating heart of countless industrial facilities, power plants, and heating systems worldwide. These complex engineering marvels are designed to convert water into steam by applying heat energy, a process that powers turbines, sterilizes equipment, and provides essential thermal energy for manufacturing. Understanding the intricate structure, thermodynamic operating principles, and the vast industrial scope of steam boilers is essential for professionals in engineering, manufacturing, and energy management.

Steam boilers serve as the beating heart of countless industrial facilities, power plants, and heating systems worldwide. These complex engineering marvels are designed to convert water into steam by applying heat energy, a process that powers turbines, sterilizes equipment, and provides essential thermal energy for manufacturing. Understanding the intricate structure, thermodynamic operating principles, and the vast industrial scope of steam boilers is essential for professionals in engineering, manufacturing, and energy management.

Understanding the Fundamental Structure of Steam Boilers

At its core, a steam boiler is a closed vessel in which water or other fluid is heated. The structural integrity of a boiler is paramount, as it must withstand significant internal pressure and high temperatures. While designs vary by application, the fundamental architecture generally comprises several key structural elements that maximize heat transfer while maintaining safety.

The Shell and Pressure Vessel

The shell serves as the primary containment for the boiler. Constructed from high-grade steel that resists corrosion and thermal stress, the shell houses the water and steam. In cylindrical boilers, this shell is often rolled and welded to form a robust container that can handle the expansive forces generated when water transitions into steam. The design codes for these vessels are strictly regulated to prevent catastrophic failures.

The Combustion Chamber

Also known as the furnace, the combustion chamber is where the chemical energy of the fuel is converted into heat. Depending on the fuel source, natural gas, oil, coal, or biomass, the design of the combustion chamber varies to optimize airflow and flame propagation. The walls of the furnace are often lined with refractory materials or water-filled tubes to absorb the intense heat and protect the structural steel from melting.

Heat Exchanger Tubes

To facilitate heat transfer from the combustion gases to the water, boilers use a network of tubes. These tubes dramatically increase the surface area available for heat exchange. The arrangement of these tubes defines the two primary categories of boilers: fire-tube and water-tube, which dictate the flow path of the hot gases and the water.

Operating Principles: How Steam Generation Works

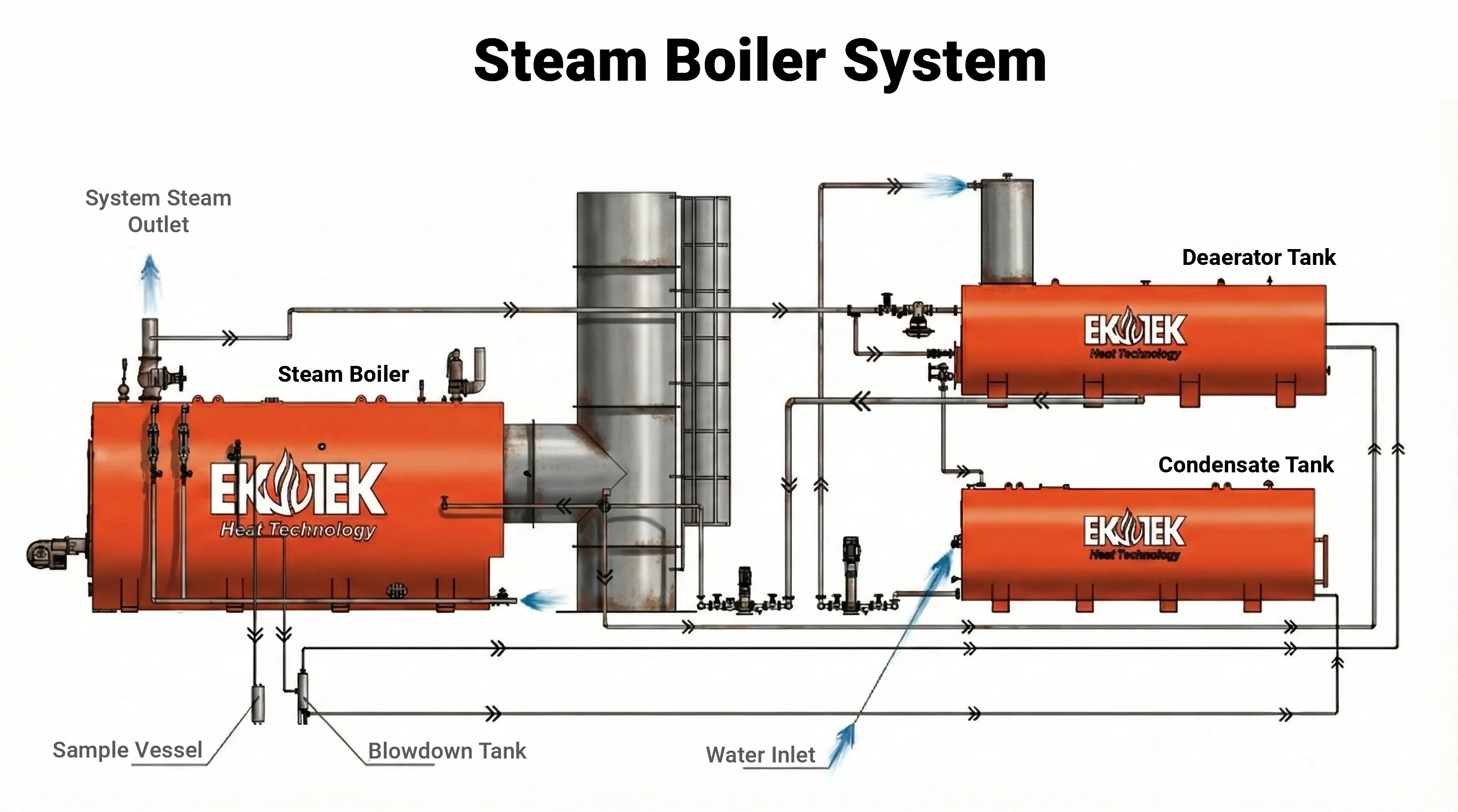

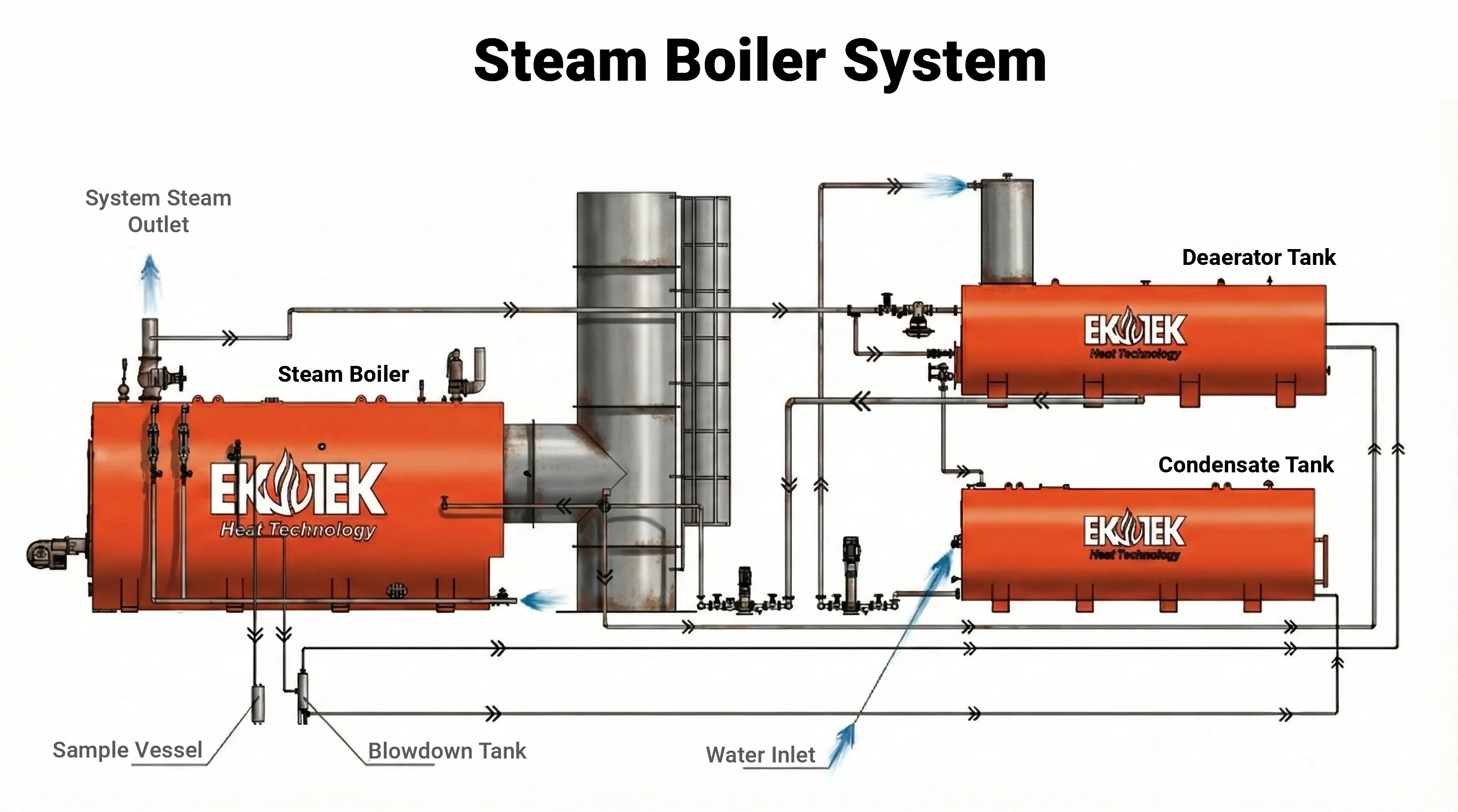

The operation of a steam boiler relies on the principles of thermodynamics and heat transfer. The process begins with the feed water system supplying water to the boiler, which is then regulated to maintain a specific level. Simultaneously, the fuel system feeds the burner to create combustion.

Combustion and Heat Release

When fuel is ignited in the combustion chamber, an exothermic reaction occurs, releasing high-temperature gases. This heat is transferred to the water through three primary mechanisms:

- Radiation: Direct heat transfer from the flame to the furnace walls and tubes.

- Convection: The flow of hot flue gases over the heat exchange surfaces, transferring thermal energy to the metal surfaces.

- Conduction: The passage of heat through the metal thickness of the tubes or shell to the water on the other side.

Phase Change and Pressure Build-up

As the water absorbs heat, its temperature rises until it reaches the boiling point corresponding to the vessel's internal pressure. At this stage, water undergoes a phase change, turning into steam. Because steam occupies a much larger volume than liquid water (approximately 1,600 times greater at atmospheric pressure), the generation of steam within a confined space creates significant pressure. This pressurized steam is then collected in a steam drum or the upper portion of the shell before being distributed to the system.

Classifications of Steam Boilers

While there are many specialized types of boilers, the industrial landscape is dominated by two main configurations, each suited for different pressure requirements and steam capacities.

Fire-Tube Boilers

In fire-tube boilers, hot combustion gases pass through a series of tubes that are surrounded by water within the main shell. These are typically used for lower-pressure applications and smaller steam capacities. They are robust, easier to operate, and generally more compact, making them ideal for institutional heating and small-scale manufacturing processes.

Water-Tube Boilers

Water-tube boilers reverse the configuration; water flows inside the tubes while the hot combustion gases circulate around the outside. This design allows for much higher pressures and larger steam capacities because the pressure is contained within small-diameter tubes rather than a large shell. Water-tube boilers are the standard for power generation and large industrial applications that require high-pressure, superheated steam.

Key Components and Accessories

A boiler is not a standalone unit but an assembly of critical components that ensure efficiency and safety. These mountings and accessories are legally required in most jurisdictions.

- Safety Valves: These are the most critical safety devices, designed to automatically open and release pressure if it exceeds the safe working limit, preventing explosions.

- Water Level Indicators: These provide a visual indication of the water level inside the boiler. Running a boiler with insufficient water can lead to overheating and structural failure.

- Pressure Gauges: These instruments indicate the internal pressure of the steam, allowing operators to monitor performance.

- Economizers: Located in the exhaust stack, economizers preheat the feed water using waste heat from the flue gases, significantly improving thermal efficiency.

- Blowdown Valves: These allow sediment and concentrated impurities to be removed from the bottom of the boiler, preventing scale buildup.

Industrial Importance and Applications

The versatility of steam as an energy transfer medium makes boilers indispensable across a wide range of industries. Steam carries a high amount of energy per unit of mass, is non-toxic, and can be easily controlled.

Power Generation

The most prominent application of high-pressure steam boilers is in thermal power plants. Here, boilers generate superheated steam that drives turbines connected to electrical generators. Whether fueled by coal, nuclear fission, or natural gas, the boiler remains the primary energy conversion unit in the cycle.

Manufacturing and Processing

In the textile, paper, and food processing industries, steam is used for heating, drying, and cooking. For example, in paper manufacturing, large steam-heated rollers dry the paper pulp. In the food industry, steam is used for sterilization and pasteurization, ensuring products are safe for consumption.

Chemical and Petrochemical Industries

Refineries and chemical plants use steam not only for heating reactors and distillation columns but also as a reactant in processes such as steam cracking. The precise temperature control offered by steam systems is vital for maintaining the delicate chemical balances required in these operations.

Efficiency and Maintenance Considerations

Modern industrial demands place heavy emphasis on energy efficiency and environmental sustainability. Boiler efficiency is a measure of how effectively the chemical energy in the fuel is converted into useful thermal energy in the steam. Factors such as incomplete combustion, radiation losses, and high stack temperatures can reduce efficiency.

Maintenance plays a pivotal role in sustaining boiler performance. Water treatment is perhaps the most significant aspect of maintenance. Untreated water contains dissolved minerals that precipitate out as scale on heat transfer surfaces. This scale acts as an insulator, reducing heat transfer efficiency and causing the metal underneath to overheat and fail. Furthermore, dissolved oxygen in feed water can cause rapid corrosion of the boiler internals. Consequently, rigorous water chemical treatment and deaeration are standard practices.

Regular inspections are also mandatory to detect fatigue cracks, corrosion, or seal failures. Non-destructive testing methods, such as ultrasonic thickness testing and X-ray imaging, are frequently used to assess the condition of boiler tubes and the shell without causing damage.

As industries continue to evolve, the technology surrounding steam boilers advances toward greater automation, lower emissions, and higher thermal efficiency. Innovations in burner technology and digital control systems enable precise modulation of fuel-to-air ratios, minimizing waste and reducing the carbon footprint of industrial operations. Despite the rise of alternative energy sources, the thermodynamic advantages of steam ensure that boilers will remain a cornerstone of industrial infrastructure for the foreseeable future.

Ultimately, the safe and efficient operation of steam boilers requires a deep appreciation of their structural limits and operating principles. By adhering to strict maintenance schedules and embracing modern efficiency technologies, facilities can ensure reliable energy production while safeguarding personnel and equipment from the immense pressure within these pressure vessels.

Steam boilers serve as the beating heart of countless industrial facilities, power plants, and heating systems worldwide. These complex engineering marvels are designed to convert water into steam by applying heat energy, a process that powers turbines, sterilizes equipment, and provides essential thermal energy for manufacturing. Understanding the intricate structure, thermodynamic operating principles, and the vast industrial scope of steam boilers is essential for professionals in engineering, manufacturing, and energy management.

Steam boilers serve as the beating heart of countless industrial facilities, power plants, and heating systems worldwide. These complex engineering marvels are designed to convert water into steam by applying heat energy, a process that powers turbines, sterilizes equipment, and provides essential thermal energy for manufacturing. Understanding the intricate structure, thermodynamic operating principles, and the vast industrial scope of steam boilers is essential for professionals in engineering, manufacturing, and energy management.